Photos

What's New

FlatFire Story

FlatFire Specs

FlatFire Team

Articles

News Releases

Links

Contact Us

[ Home ]

[ FlatFire Team ]

©2002 Main Attractions -- All rights reserved

APOCALYPTIC |

Analyzing

By Gray Baskerville |

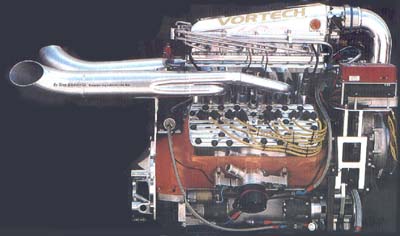

The missing link was the electronic connection that ties all these elements together. Todayís computer-controlled, programmable EFI, coupled with 12 psi of Vortech-generated boost augmented by 600 hours of Mike Landyís engine building experience made it happen. Think of it. Transforming an 85hp passenger car engine into a 1.8hp-per-inch powerplant is incredible. And this is how it went down. In 1990, Ron Main got it in his head to make a "hero run" down Bonnevilleís vast race land behind the wheel of his flathead-powered highboy. Main was bedeviled by an apparent contradiction the man who claims never to have left the í50s wanted to retro-fit his flat motor with í90s thinking. Over the years, Main had employed the services of Dick Landy Industries in an ongoing quest for more power. When his "flat-nasty" project materialized 10 years ago, DLI got the mission impossible call modernize an engine that was already deemed obsolete in 1932, the year Ford began manufacturing the nationís first mass-produced V-8. Dick, Mike, and Robert Landy plus the boyz in the back room developed a series of record-breaking flatheads. A decade later, Main has teamed up with Jim Middlebrook (Vortech Engineering), Ernie Cross (Ventura Speed and Marine), and Bruce Crower (Crower Cams) to assemble what they hope to be the first 300-mph flat attack. BlockheadsFlatheads for all you rodders who arrived after 1953, the year Ford killed the old boiler arenít like your belly-button Chevrolets. Chevys are overhead-valve engines. Flatheads have the valves in the cylinder block next to the bore. Nonetheless, the side-valve engine is very clean-burning and fuel-efficient, and provides a wonderful brake-specific fuel curve. Their problem is lack of airflow, which kills the flatheadsí ability to produce peak power. Landy claims that the best flatheads canít outflow the worst overheads. Lots of combustion chamber surface, and routing the exhaust passages around the cylinder bores through the water jacket and out the side of the block, didnít help the cooling situation, either. Rodders begain to experiment. They redirected the exhaust gases out the intake ports or bored into the exhaust passages and redirected the exhaust gases out the top and ends of the block . . . with varying degrees of success. Landy took it one step further. He switched ports.  The only vestige of the original animal is the radically reworked cylinder block. |

|

|

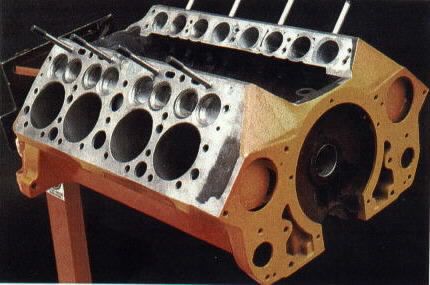

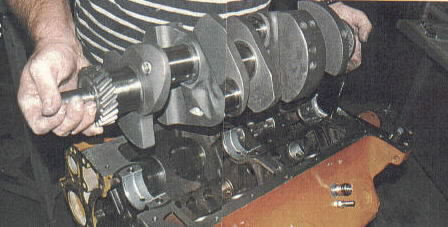

The original intake passages now channel the exhaust directly out the intake port; the rerouted but leak-prone exhaust passages now contain the cool intake mixture. Reversing the ports required a "blocklobotomy." The 59AB block (cast in 1947) was sonic-tested for core shifts. Then a portion of the intake passages at the machine pad at the top of the valley-housing was milled off to give Landy better access to the exhaust passages located inside the block adjacent to the water jackets. Portions of the exhaust passages were bored into, and the balance welded up and filled with epoxy to help stabilize the top of the block. Landy formed new intake passages next to the Ďold/newí exhaust ports and reshaped them with epoxy. The beauty of this reverse-flow technique is that the intake-turned-exhaust ports remain as cast. Even though the radically altered cylinder block was subsequently heat-treated and stress-relieved, welding-induced warpage had moved all the machined surfaces 0.020-inch off register. After the block was sonic-checked for a second time, Landy re-machined the decks, pan rails, bearing saddles, cylinder bores, and the like. The bore was opened up from 3.1875 to 3.307 inches .ind Landy-built billet steel main caps were installed High End Lower EndAnother one of the flatheadís weaknesses is the overall strength of its lower end assembly likely a by-productof Depression-generated economics and Henry Fordís love of simplicity. Fordís one-piece cast block (an industry first) had three main bearing saddles. With a 3.750-inch stroke, skinny 7-inch-long rods and cast 6.8:1 pistons, Hankís primitive pump was good for 100 horses at 3,800 rpm in 1947. But you need more than 239 inches and 100 horses to go 300. First Landy used a billet, 4.375-inch Moldex stroker crankshaft to increase the engineís displacement from 239 to 301 ci. He stipulated 327ci Chevy rod journals, front snout, and rear flange to facilitate finding replacement parts. Then he added the billet steel main caps and put four bolts in the center one. Bruce Crower chipped in stock-length, billet steel rods designed to accept Chevy rod bearings. The funny-looking cast pistons have been replaced with mild-dome, three-ring, forged aluminum Ross slugs. Crower PowerCrower supplied an "inverted radius" roller cam a single-pattern stick featuring reversed intake and exhaust lobes to produce 0.435-inch net lift and 276 degrees of duration at 0.050-inch. The 1.80-inch intakes and 1.60-inch exhausts arc actually cut-down 2.02-inch Manley titanium valves. The seat pressures generated by its K-Motion valve springs are 295 pounds open, 165 pounds closed. Heads UpOld-time rodders attempted to increase airflow by relieving the block reducing the deck height around the valves. The reader will note that there is no deck relief around the vaives of the Millennium Monster. On the other hand, the cylinder head modifications include enhanced cavity work in the intake valve pockets and a tightening around the exhaust valve pockets. Landy machined these Finned aluminum castings (produced by Tony Barron, the son of hot rod pioneer Frank Barron) to accept dual spark plugs. According to Landy, Barronís 24-stud "flatheads" operate under the same cylinder pressures generated by 1,200hp Pro Stock engines. They have also been grooved to accept 0.030-inch copper wire, and the combustion chambers have been remachined. Well OiledAs you might have guessed, exceptionally good oil control and heat dissipation is paramount for an engine asked to run full throttle for 5 miles, especially one with three mains and Pro Stock-style cylinder pressure. A dry sump system employing a multi-stage Avaid pump, a specially formcd pan, and a tank containing four gallons of Valvoline 20/50 oil do the job (max oil pressure is 70 psi). Flat FiringA dual-plug head generally requires twin magnetos. Landy began with a pair of Mallory Super Mags, but ran into trouble getting them to send a clear signal to the Accel digital fuel injection. He converted one of the mags into a distributor by removing the generator and letting the points trigger the MSD ignition module. There is 20-degrees lead in the mag and between 15 and 20 in the "magstributor." Blowing in the WindBoth Main and Landy felt they needed at least 550 hp to go 300 mph at Bonneville. A normally aspirated flathead worked to the gills with nitro or nitrous canít flow enough air and fuel to generate such power. Turbochargers presented a packaging problem. A crank-driven Roots-type blower builds instant torque but extracts a great deal of power to turn the rotors. So Main split the difference and employed a modern, crank-driven centrifugal supercharger manufactured by Vortech Engineering. Those familiar with the Jimmy Keenís NMCA Super Street Mustang know that itís powered by a Vortech-blown block. The Vortech makes a lot of top-end boost without taking a lot of power to drive it. Main chose its T-trim unit and has it overdriven to produce 12-psi boost at 6000 rpm, which is about as tight as you ever want to turn a flat motor. Injection Is Nice, TooA supercharger compresses air, which causes heat. So Main had Ernie Cross fabricate a plenum chamber feeding into eight DLI-built runners fitted with individual injector nozzles capable of flowing 96 pounds of fuel per hour and housing a four-section Spearco intercooler. The programmable Accel EFI controls fuel delivery and spark signal, and even though this highly sophisticated fuel delivery system precisely meters the incoming fuel charge. Landy spent a lot of time reading plugs to make sure that the injectors were delivering the proper air/fuel mixture. Though Fordís fabulous flathead was declared dead 45 years ago, a victim of the OHV revolution, this ainít necessarily so. A contemporary Main, Landy, Middlebrook, Cross, and Crower race-lift may have done what we poor mortals felt was impossible building an apocalyptic flathead. May it live forever! |

Landy milled the top of the valley off to expose the intake and exhaust passages. The reshaped passages on either end of the block and in the center have become the intake ports. The original intake passages between the reworked ports are now the exhausts.

Note how the new ports were shaped, how the 24-7/16 inch studs are located around the cylinder bore, and that the valves have not been relieved. Landy calls the original Ford castings "superb."

Bruce Crower thinks veteran cam grinder Chet Herbert may have done some flathead roller cams in the í50s, but he couldnít remember who ran them. His rollers combine with a 0.435-inch lift. A grove milled on the inside of the lifter bore picks up the nipple on the side of the one-off Landy lifters and locks them in place. (Crower now sells similar roller lifters for flatheads.)

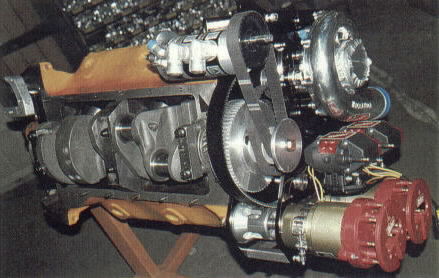

The millennium millís lower end is a study in billet mania and includes a Ĺ-inch stroker Moldex crank and 4340 steel Crower rods, heat-treated to 180,000 psi, and the DLI-machined four-bolt center main. Splayed outside bolts enter a virginal portion of main web. The 7.5:1 Ross forged aluminum pistons feature a slight dome and 0.750-inch pins.

Although these DLI-modified Barron castings have been totally reworked, a 24-stud flat-headís basic strength is the eight head studs surrounding the cylinder bores and nuts that are torqued to 65 psi. As such, they are able to contain the same cylinder pressure generated by a Pro Stock engine.

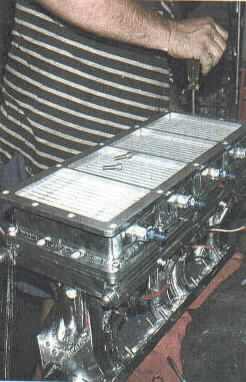

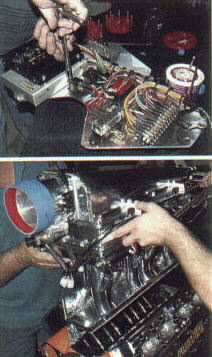

Ernie Cross (Ventura Speed & Marine) was responsible for the unique induction system. Cross built the blower drive, mag drive, and top portion of the injection including the inter-cooler. Even though the engine burns alky, the intercooler reduces inlet temperature further.

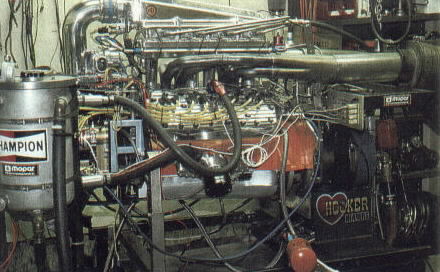

The millennium monsterís induction mixes new-old centrifugal supercharging and intercooling with a sheetmetal intake manifold, a throttle body, and electronic fuel injection.  Flatheads are chronic wheezers: The intake and exhaust gases must make a U-tum to enter and exit the combustion chamber.

Crankshaft is supported by a trio of billet main caps; the photo illustrates how the dry sump pump, blower, and mags are driven.

DLI handled the bottom portion of the injection, including the inlet tubes, nozzle bosses, and fuel rails. Software for the Accel DLI system allows Landy to adjust the fuel mixture and spark lead with a computer.

The first dyno tests were conducted with a Vortech R-trim blower. DLI later switched to a smaller T-trim for improved engine longevity. Regardless, Millennium Monster generated 566 hp at 5,700 rpm and 512 lb-ft of torque at 4,900. Due to poor traction, the 12-psi boost was reduced to 4 and produced a 232-mph pass with a 237-mph exit speed (among the fastest terminal speeds ever recorded by a flathead-powered car). The following run with more boost and gearing for 270 ended when the uneven course caused the car go out of control and suffer extensive damage. They will return to Bonneville next year.

|